Legal Literacy - Eradication corruption has always been the most loudly heard political promise in every change of national leadership. At the beginning of his administration, President Prabowo Subianto demonstrated a very strong verbal commitment to this agenda. In various speeches and public statements, he affirmed his determination to enforce the law impartially and to eradicate corrupt practices that have been undermining the country. The message was conveyed in a firm and confident tone, fostering public hope for the presence of a courageous and decisive leadership.

As time goes by, unease arises in the public sphere regarding the extent to which this commitment is truly realized in practice. This is where the public begins to see a gap between political statements and implementation on the ground. Corruption is not merely a matter of rhetoric, but rather a matter of courage to take political risks, consistency in law enforcement, and willingness to dismantle the networks of power that have been protecting the perpetrators.

Controlled Central Corruption and Stalled Old Cases

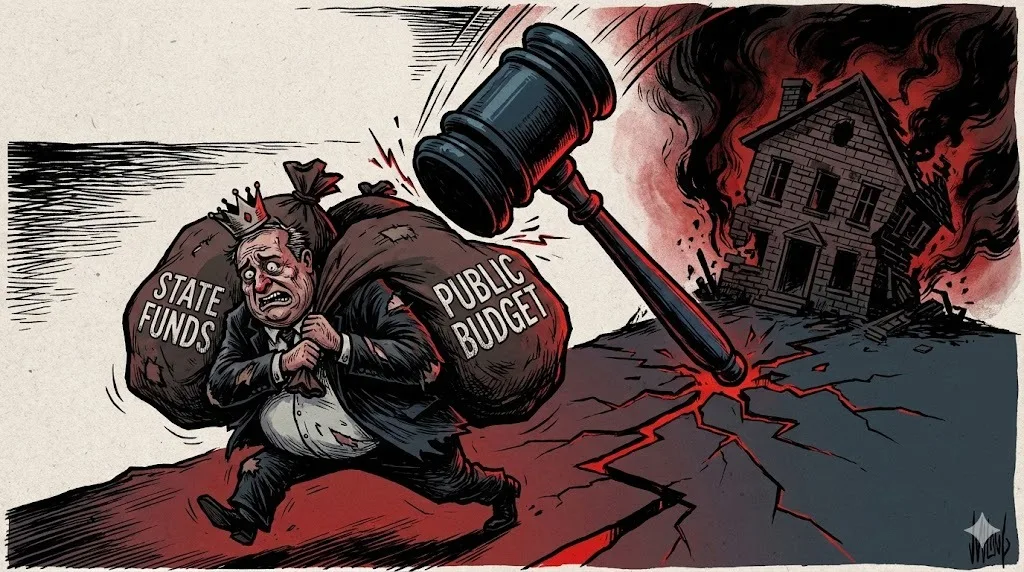

An interesting phenomenon is the near absence of new large-scale corruption cases at the central level. This condition is often referred to as a controlled situation. However, the availability of major cases does not necessarily indicate improved governance. It could be that corruption is becoming more organized and protected. Ironically, the handling of old cases appears to be stalled, as if losing priority and direction for resolution. Corruption at the central level generally involves actors with strategic positions, extensive political networks, and the ability to influence legal processes. Therefore, the absence of major cases does not necessarily reflect the success of corruption eradication, but may indicate the increasing strength of political and bureaucratic protection mechanisms.

In conditions like these, the law risks losing its reach when faced with the interests of the elite. While new cases appear minimal, the handling of old cases is experiencing a significant slowdown. A number of major legacy cases are stalled, unresolved, or have lost their law enforcement momentum. This situation gives the impression that resolving old cases is no longer a priority, even though these cases should be the entry point for uncovering systematic corruption patterns. The stagnation in handling old cases also has a serious impact on public trust. When the legal process proceeds slowly without clarity, the public will tend to judge that the state is hesitant or unwilling to touch the major actors involved. If this condition is allowed to continue, the narrative of controlled corruption has the potential to turn into the normalization of impunity at the central level.

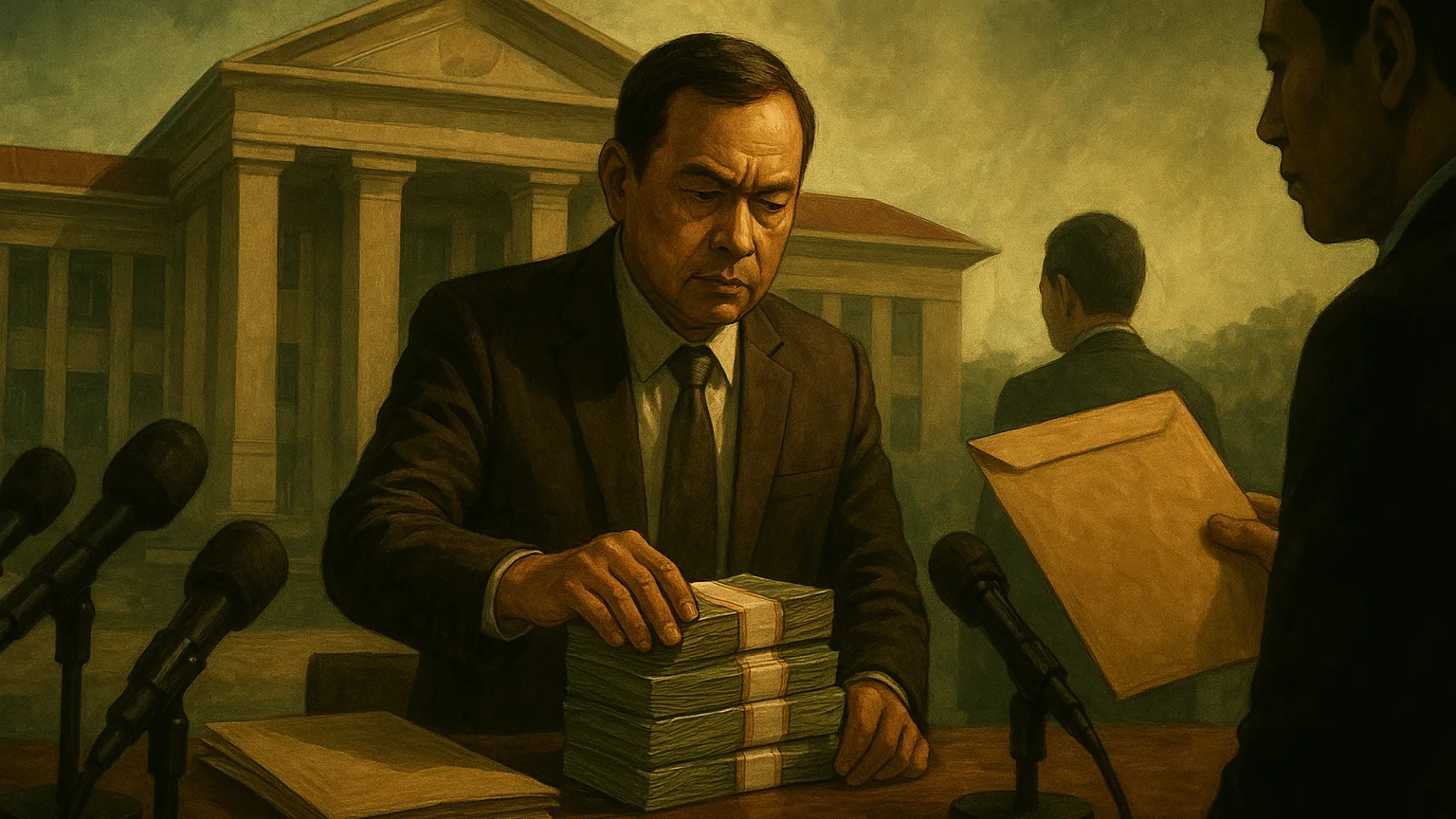

KPK and Skewed Law Enforcement

The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) is once again in the spotlight. This institution still records achievements through Sting Operations (OTT), especially against regional heads and law enforcement officials in the regions, including several prosecutors. However, in handling major cases at the central level, the KPK is considered to appear weakened. This condition gives the impression that the courage of the anti-corruption agency is no longer as strong as before. The critical view of this condition is in line with the opinion of Prof. Mahfud MD, an expert in constitutional law and former Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs.

Mahfud has repeatedly emphasized that corruption eradication in Indonesia often stalls not because of a lack of legal rules, but because of a weak political will. According to him, the law is often sharp downwards but blunt upwards, especially when corruption cases are considered to touch the power elite and political interests.

Mahfud also emphasized that corruption can never be seriously eradicated if law enforcement is still compromised by the interests of political stability. On various occasions, he mentioned that the state actually has strong legal instruments, but the courage to execute them is often defeated by short-term political considerations.

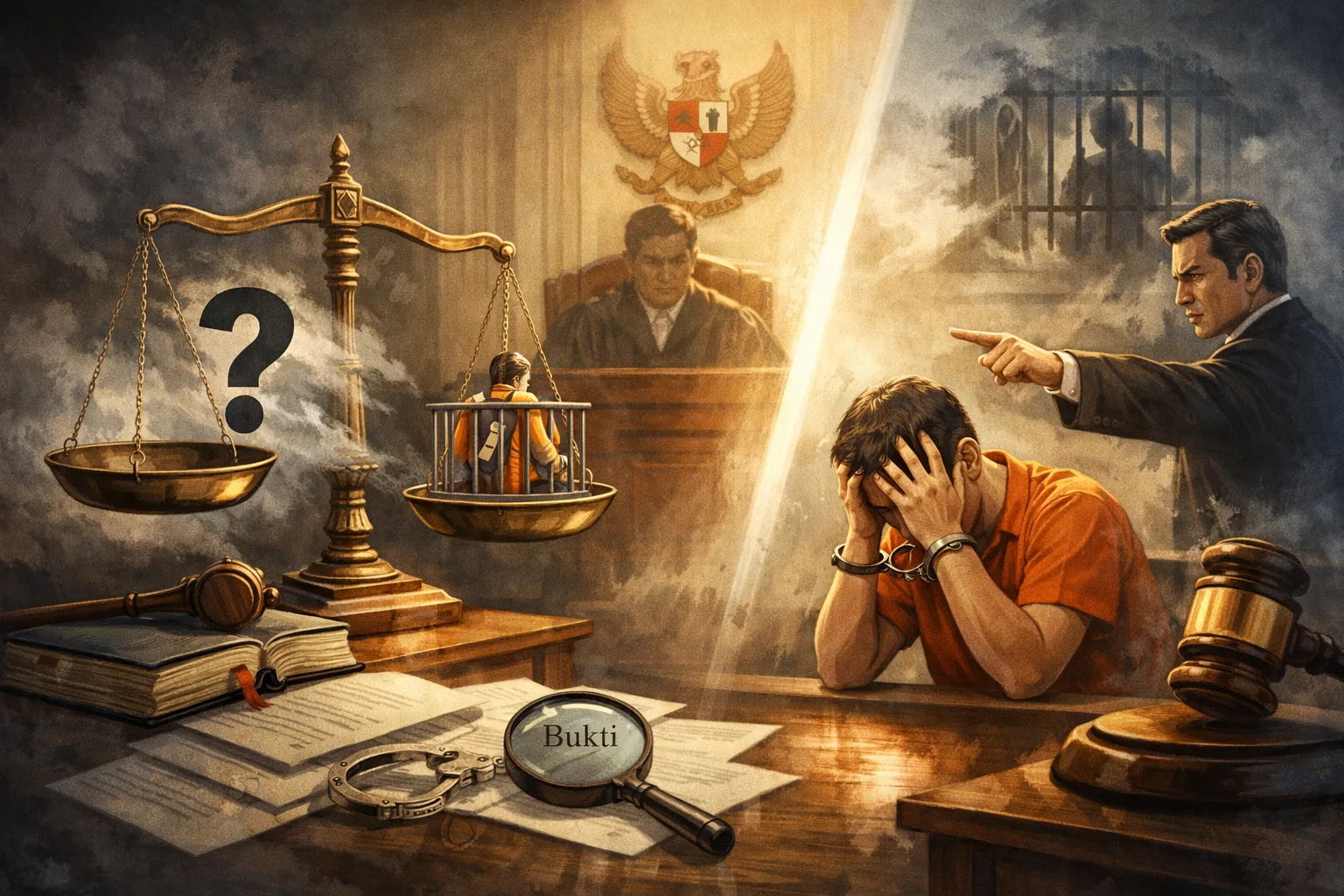

The case of sea fences is a real example of law enforcement that is considered incomplete. The handling only touches perpetrators at the village or local level. In fact, the issuance of many illegal state land certificates is almost impossible without the involvement of major actors with access to power and bureaucracy. When the law stops at the lower level, the public naturally questions the state's seriousness in uncovering the main perpetrators.

Strategic Projects and Inconsistent Case Handling

In the Whoosh High-Speed Train project, President Prabowo took a step by taking responsibility abroad to maintain the country's credibility. However, this step has drawn criticism because it has not been accompanied by a thorough internal investigation into allegations of cost overruns and procedural problems involving many parties, including the House of Representatives. Without legal transparency, efforts to save the project risk being perceived as a disregard for accountability. The case involving Pertamina adds to public anxiety. The inconsistency of the charges, from the issue of mixed oil which then shifted to contract manipulation, raises confusion and suspicion. Beyond that, the stalled handling of the Hajj quota and Bank BJB cases further reinforces the impression of weak consistency in law enforcement against major cases.

Political Burden and the Direction of Corruption Eradication

The stalled eradication of corruption is often associated with political burdens or landmines. The President is in a dilemma between enforcing the law firmly and maintaining political stability and the ruling coalition. However, it is precisely at this point that leadership is tested, namely the ability to place law above political interests. Throughout 2025, the practice of making or changing legal rules with minimal meaningful public participation is still visible. Regulations that are drawn up hastily and in secret have the potential to become a tool to cover up certain policies. This practice weakens the principle of the rule of law and opens the door for abuse of power.

In the end, the public does not demand perfection, but consistency and courage. President Prabowo has strong political capital to make breakthroughs in eradicating corruption. If the gap between promises and reality continues to be allowed, public trust will be further eroded. On the other hand, the courage to resolve old cases, strengthen the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), and stop the manipulation of regulations can make this verbal commitment a real legacy for law enforcement in Indonesia.

Comment (0)

Write a comment