Legal Literacy - In our constitutional law landscape, the President not only holds governmental power (pouvoir executif), but also grasps the remnants of royal power that we know as prerogative rights. Article 14 of the 1945 Constitution mandates the President to grant clemency, rehabilitation, amnesty, and abolition. On paper, this authority is a safety valve—an emergency exit when the justice system fails to provide a sense of substantive justice. However, recent phenomena indicate a worrying shift. This extraordinary right seems to be metamorphosing into a "cover-up" instrument for law enforcement chaos, especially in corruption cases.

We often witness the President intervening to grant amnesty or abolition to certain figures involved in corruption cases, or cases that are "forced" into corruption. Indeed, on the one hand, the public—and perhaps some of us—breathe a sigh of relief. There is a sympathetic argument that not everyone dragged into the corruption court (Tipikor) is a criminal who robs state money. Many of them are victims of "criminalization of policy" or administrative errors that are forcibly drawn into the criminal realm by law enforcement officials who are chasing deadlines. In this context, the President's move looks heroic; like a "Just King" who restores the good name of those who are oppressed by a rigid system.

However, if we examine this issue with clearer legal glasses, this habit harbors a latent danger. Using prerogative rights to resolve cases deemed "out of place" or "unworthy of trial" is a shortcut (shortcut). And like a shortcut on a steep terrain, it never fixes the main road that is damaged. This habit actually confirms that our legal system is seriously ill, and instead of treating the disease, we are only busy giving painkillers.

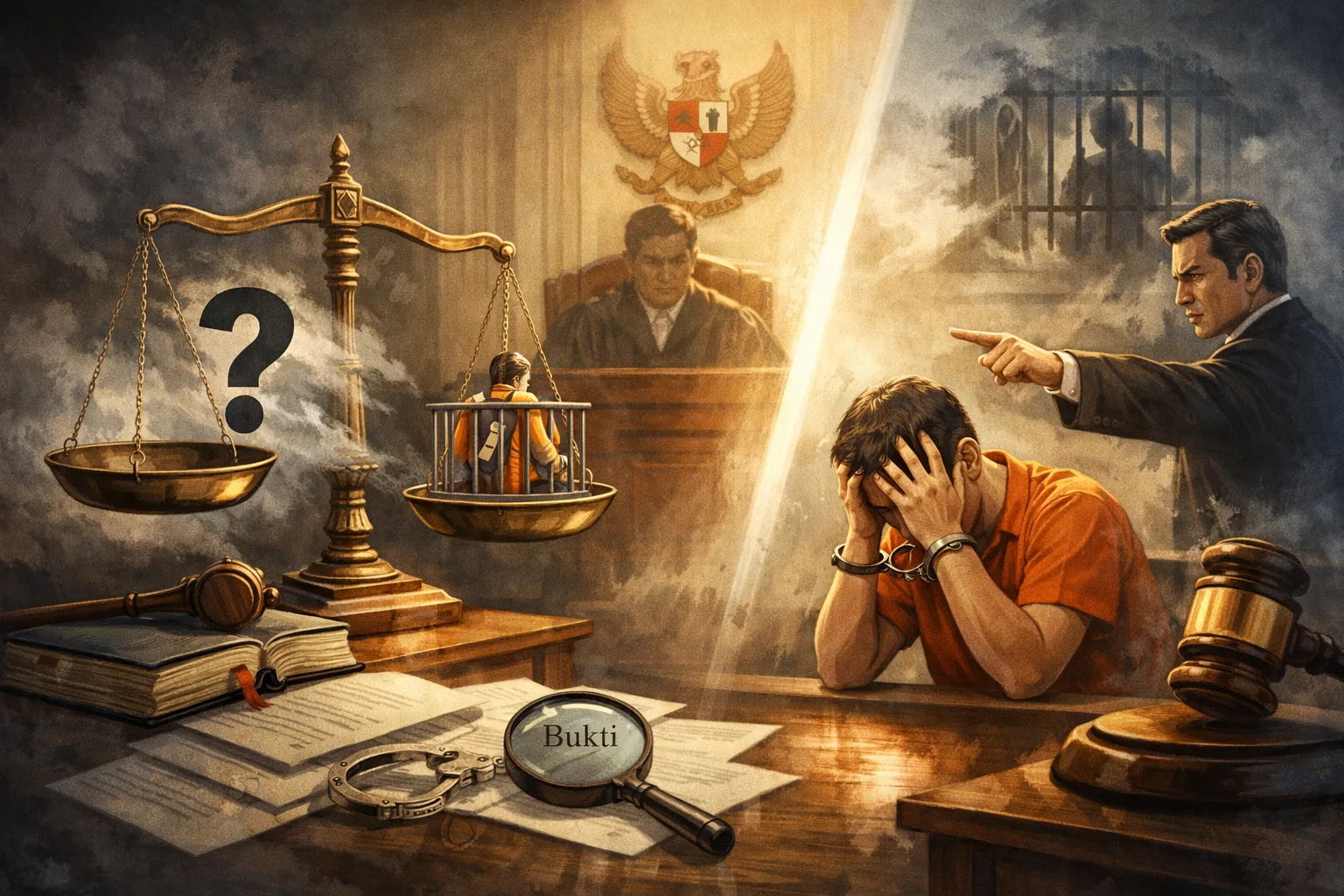

The Illusion of Justice

The fundamental problem with using amnesty and abolition as instant solutions is the creation of an illusion of justice. When the President grants pardon or termination of prosecution, it does save one individual, but leaves thousands of other potential victims under the threat of the same regulations. This action is casuistic and very political. The question then is, what about those who experience a similar fate—criminalized for administrative policies—but do not have access to the palace? What about regional officials or policymakers who are not viral on social media so they escape the President's radar?

Law, in the ideal of the rule of law (Rechtsstaat), must work impersonally and systemically. Justice should not depend on the generosity of a ruler, but on the certainty of a fair system. When the President is too diligent in intervening in the legal process—even with good intentions—it indirectly degrades the authority of the judiciary. As if there is absolute distrust from the executive towards the judiciary's ability to decide cases fairly.

Furthermore, this pattern creates moral hazard. Law enforcement officials (Police and Prosecutors) will never feel the need to improve their investigation and prosecution standards. They will continue to use "blinders" in applying the elastic articles in the Corruption Law, because if there is a case that is too controversial, the President will fix it at the end of the road. This is a vicious circle that spoils law enforcement officials to be unprofessional and allows bad regulations to continue to exist. We are trapped in the romanticism of a savior figure, while forgetting that we need a system that saves.

Systemic Damage

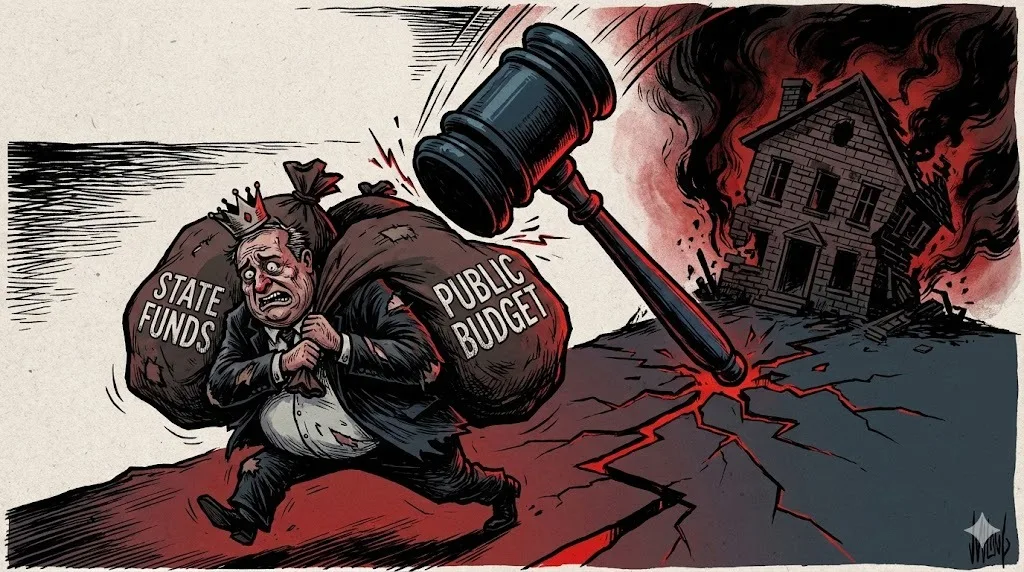

A frequently used justification for the President's actions is that the case does not merit being in the realm of corruption crimes. For example, an official's discretion that does not benefit themselves but harms the state due to external factors is often attacked with Article 2 or Article 3 of the Anti-Corruption Law. This is where the root of the real problem lies. If we agree that the act does not deserve to be criminalized, then the fault lies not only with the fate of the defendant, but with the legal formulation.

The use of amnesty and abolition in cases like these is a tacit admission by the state that our Anti-Corruption Law is problematic. There is over-criminalization there. There is a blurring of the lines between state administrative law and criminal law. However, the state's response is paradoxical. Instead of conducting a legislative review or revising the law, the President chooses to use his prerogative. This is like patching a flat tire with duct tape while the nail is still stuck in it.

Ideally, that great political energy should be directed towards fixing the root of the problem. The President, as the holder of legislative power together with the DPR (Article 5 paragraph (1) jo Article 20 of the 1945 Constitution), has instruments that are far more powerful and have a long-term impact than just amnesty.

This condition is exacerbated by the overlapping of our legal regimes. The Law on Government Administration actually provides a corridor that administrative errors must be resolved administratively, not criminally (the principle of ultimum remedium). However, in practice, law enforcement officials often ignore the Law on Government Administration and immediately jump to the Anti-Corruption Law. If the President wants to protect state apparatus and its citizens from criminalization, the right step is to order the Attorney General and the Chief of Police (who are directly under his command) to create strict prosecution guidelines, or issue a Government Regulation that reinforces these boundaries. Not by waiting at the end of the process and giving a "gift" of forgiveness.

Total Reform

It is time for us to stop idolizing shortcuts. The solution to the mess in corruption law enforcement—where innocent people can get caught up—is legal reform, not a clearance sale on forgiveness. The President must dare to take an unpopular but strategic step: leading the reform of corruption crime regulations.

The first thing to do is to revise the articles in the Anti-Corruption Law that have been the entry point for criminalizing policies. The element of "detriment to state finances" must be strictly redefined so that it does not target losses that are administrative or purely business risks. Second, the President must ensure that the harmonization between the Anti-Corruption Law and the Law on Government Administration works at the implementation level. Law enforcement officials must be forced to submit to the internal oversight mechanisms of government officials (APIP) before moving into the criminal realm.

If the President continuously uses amnesty and abolition as solutions, we are concerned that the presidential institution will turn into a kind of "counter Supreme Court" that decides cases based on political discretion, not juridical considerations. History records that excessive power in granting pardons without being balanced by system improvements will only create new legal uncertainties.

In the end, the best legacy (legacy) of a President is not how many people he saves from prison through a piece of Presidential Decree, but how solid the legal system he builds so that no more innocent people go to jail. We long for a country where justice is present through the judge's gavel and the clear sound of the articles of law, not through the golden ink of clemency or amnesty that is anxiously awaited. Stop this "habit" of shortcuts, and start repairing our legal highway that has been damaged and riddled with potholes for too long.

Comment (0)

Write a comment