Legal Literacy - Criminal law is often seen as a technical instrument of the state—a catalog of prohibited acts accompanied by the threat of sanctions. However, behind the rigid articles and procedures, lies a deep philosophical foundation about the nature of man, society, and

justice itself. At its heart, criminal law is a stage where the state exercises one of its most fundamental and frightening powers: the power to deprive its citizens of their liberty, property, and even life. The question then is not "what is criminal law?", but "why does the state have the right to punish?" and "what is the meaning of punishment itself?"

This article will delve into the philosophical foundations that underpin the modern criminal law system.

Social Contract: Legitimacy of Power to Punish

Every discussion about state authority cannot be separated from the theory of social contract, which was popularized by Enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In a state of nature (

state of nature), each individual possesses absolute freedom, yet lives in fear and uncertainty. To achieve security and order, individuals consciously (or implicitly) surrender some of their freedom to a sovereign entity, namely the state.

This is where the first legitimacy of criminal law lies. When someone commits a crime, they not only harm the victim individually, but also tear apart the social order that has been mutually agreed upon. They violate the "contract" that underlies the existence of a safe society. Therefore, the state, as the guardian of that contract, has the right and even the obligation to respond to that violation through a mechanism of punishment. Criminal punishment, in this framework, is a logical consequence of the denial of the collective agreement to live together peacefully.

The Soul of Punishment: Why Do We Punish?

After the state's legitimacy to punish is established, the next philosophical question arises: what is the purpose of that punishment? Here, we are faced with two main poles of thought that have shaped the debate for centuries.

1. Retributive Theory (Deontological): Punishment as Absolute Justice

This view, rooted in the thinking of Immanuel Kant, sees punishment not as a means to achieve another goal, but as an end in itself. Punishment is a commensurate retribution (

just desert) for the wrong that has been committed. A person is punished because they

deserve it.

Philosophically, retributivism values the perpetrator of a crime as a rational moral agent with free will (

free will). By committing a crime, they have made a choice. Punishing them is a way of respecting that choice by imposing fair consequences. For Kant, not punishing a criminal is a form of injustice, because it means denying their moral responsibility. This view is backward-looking (

backward-looking); the focus is on the act that has occurred, without the need to think about its impact in the future. The ancient adage

lex talionis ("an eye for an eye") is an echo of this retributive spirit.

2. Utilitarian Theory (Consequentialist): Punishment as a Tool for Social Welfare

In contrast to retributivism, utilitarianism—pioneered by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill—is

forward-looking. Punishment can only be justified if it produces better consequences for society as a whole. Punishment is an "evil" that is justified because it can prevent greater evils. The goal is to maximize happiness and minimize suffering. In practice, this theory manifests itself in several objectives of punishment:

- Deterrence: Punishment aims to deter, both the perpetrator themselves from repeating their actions (specific deterrence) and the wider community from imitating similar actions (general deterrence).

- Rehabilitation: Punishment is seen as a means to reform the perpetrator, equipping them with skills and changing their mindset so that they can return to being productive members of society.

- Incapacitation: By imprisoning the perpetrator, the state physically prevents them from committing further crimes against society.

Modern criminal justice systems rarely adhere to one of these theories in its pure form. Instead, what occurs is a fusion that often creates philosophical tension: we punish someone because they are guilty (retributive), but the form and duration of the punishment are often influenced by considerations about what is best for society in the future (utilitarian).

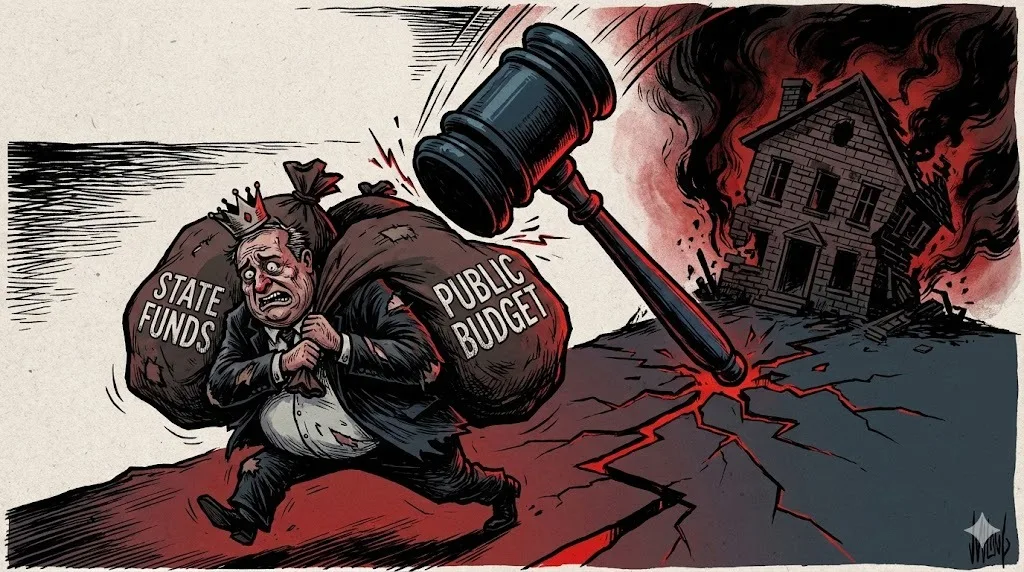

Principle of Legality: Fortress Against the Tyranny of Power

The principle of legality, which is formulated in the Latin adage

Nullum delictum, nulla poena sine praevia lege poenali (no crime, no punishment without a prior penal law), is more than just a technical legal principle. It is a philosophical manifestation of the protection of the individual against the arbitrariness of the state.

Born from the anti-absolutism spirit of the Enlightenment, this principle guarantees

legal certainty. It ensures that citizens can know with certainty what actions are prohibited, so that they can regulate their behavior. Without this principle, the state could punish anyone for any action at will. Thus, the principle of legality is not merely a rule of the game for legal experts, but a fundamental pillar of a state of law (

Rechtsstaat) that limits power in order to protect freedom.

Mens Rea: Accountability for Free Will

Criminal law does not punish evil deeds alone, but punishes the people who commit evil deeds. This difference lies in the concept

mens rea or "mens rea" (

guilty mind). We do not punish a tree that falls on a car, or an epileptic who has a seizure while driving and causes an accident. Why?

free will. We can only assign moral (and legal) responsibility to individuals whom we deem capable of choosing between right and wrong. The concept of "mens rea" is the bridge between the physical act (

actus reus) and criminal responsibility. This is why criminal law carefully distinguishes between intent (

dolus) and negligence (

culpa), and recognizes excusing reasons such as the inability to be held responsible (Article 44 of the Criminal Code).

Conclusion

Understanding criminal law philosophically means seeing it not as a collection of dead norms, but as a continuous dialogue about justice, morality, freedom, and power. It is a mirror that reflects how a civilization defines itself: how it balances collective security and individual rights, between the demands of retribution and the hope of reform, and between legal certainty and a sense of justice. For legal practitioners and academics, delving into these philosophical depths is not merely an intellectual exercise, but a necessity to ensure that the sword of justice held by the state is used wisely and responsibly.

Comment (0)

Write a comment