Legal Literacy - This article discusses the extension of authority Constitutional Court of the (MK) of Indonesia in handling general election result disputes. Through an analysis of the case of Decision Number 138/PUU-VII/2009, the author elaborates on how the MK expanded its interpretation of the constitution, set aside the principle of judicial restraint, and considered the teleological aspect in its decision. This article also explores the potential for similar applications in resolving future general election result dispute cases, as well as the juridical and political implications of the MK's more progressive approach in the context of national and constitutional law.

Addressing the Problems of the Constitutional Court (MK)

The Law regarding the MK, with the latest amendment by Law Number 7 of 2020, is a Law that receives normative attribution from the Constitution. Its position as the recipient of normative attribution sourced from the Constitution gives it privileges, including the authority to stipulate further regulations regarding certain Law materials as an extension of the Constitution. The regulations that are further regulated include the requirements to become a Justice of the MK, the election of the Chief Justice and Deputy Chief Justice of the MK, and the retirement age for Justices of the MK.

The object of normative study that needs to be highlighted is the vacuum of further regulations that touch on the realm of the MK's authority itself. As far as the author's research goes until this paper is published, no regulations in the form of Law are found that regulate such matters. The four authorities and one obligation of the MK outlined in the Constitution are derived as they are without shifts and extensions into the form of Law and Perpu (Perpu Number 1 of 2013 which was enacted into Law with Law Number 4 of 2014). This normative reality is interesting because legal products are found outside of Law and Perpu that touch on areas that are not touched by Law and also Perpu.

Legal products that are recognized by national law, and also by other legal countries, are not only dimensioned as law in abstract, in the form of Laws and their derivatives, but also dimensioned as law in concrete, in the form of court decisions or jurisprudence. In the treasury of MK jurisprudence, jurisprudence is found that touches on this realm, including Decision Number 138/PUU-VII/2009. The decision a quo can be said to be a progressive-controversial decision because it steps over several fences that in legal tradition must be obeyed by the MK.

Examining the Legal Reasoning of Decision Number 138/PUU-VII/2009

In Decision Number 138/PUU-VII/2009, the Constitutional Court considered it necessary to include Government Regulations in Lieu of Laws (Perpu) within the definition of laws that fall under the Court's authority for judicial review. This was done as an interpretation of the Constitutional Article governing the matter. Article 22 of the 1945 Constitution, which regulates Perpu, explicitly distinguishes between Perpu and laws, even though the content of both is essentially the same. The legal reasoning developed by the Constitutional Court as the basis for the decision a quo includes consideration of the implications arising from the Perpu.

A Perpu will create new legal norms that have implications for the emergence of new legal statuses, legal relationships, and legal consequences. The interval for the validity of legal norms in a Perpu is from the time the Perpu is ratified until the DPR's (House of Representatives) rejection or acceptance of the Perpu in the next session after the Perpu is issued. Thus, the Constitutional Court has the authority to review the substance of a Perpu because its binding force and content are the same as a law.

In the legal reasoning of the decision a quo, it is clear how the Constitutional Court maneuvers in viewing and interpreting the normative relationship between the Constitutional article governing the Court's authority, Article 24C, and the article governing Perpu matters, Article 22. The Constitutional Court engages in interpretative deviation, namely ignoring the principle of judicial restraint. According to Aharon Barak, this principle requires judges to interpret a law by first considering the legal politics of its formation.[1] This principle, which arises from the concept of constitutionalism, is oriented towards limiting the Constitutional Court so that it does not act as a mini parliament, pretending to be an institution authorized to create legal norms.[2]

The decision a quo is among the decisions that can be labeled "courageous" because it overrides the principle of judicial restraint. In addition, the legal reasoning of the decision a quo is characterized by teleological interpretation, ignoring the original intent in interpreting Articles 22 and 24C of the 1945 Constitution. Teleological interpretation is an interpretation oriented towards the purpose (teleology) of a regulation that is established. The application of this interpretation method still considers the interpretation rules, namely (1) verbal meaning; (2) grammatical construction; (3) the context of the legislation; and (4) the social aspects contained in the law to be interpreted.[3]

The Idea of General Election Process Disputes

As a judicial institution, in some cases the Constitutional Court often uses jurisprudence as a consideration in a decision. This occurs, for example, in Decisions Number 01-021-022/PUU-I/2003, 002/PUU-I/2003, and 058-059-060-063/PUU-II/2004. In the decision a quo, the Constitutional Court issued the same decree in all decisions so that it can be called faste jurisprudence or a fixed decision.[4]

The use of jurisprudence as a consideration in a decision can be in the form of applying a previous decision exactly to the case being handled or applying the legal reasoning that is the basis of the decision. Applying the same legal reasoning can answer legal problems that have the same characteristics. A judge can use the legal reasoning of a previous decision if the judge considers that the legal reasoning can answer the case being faced.

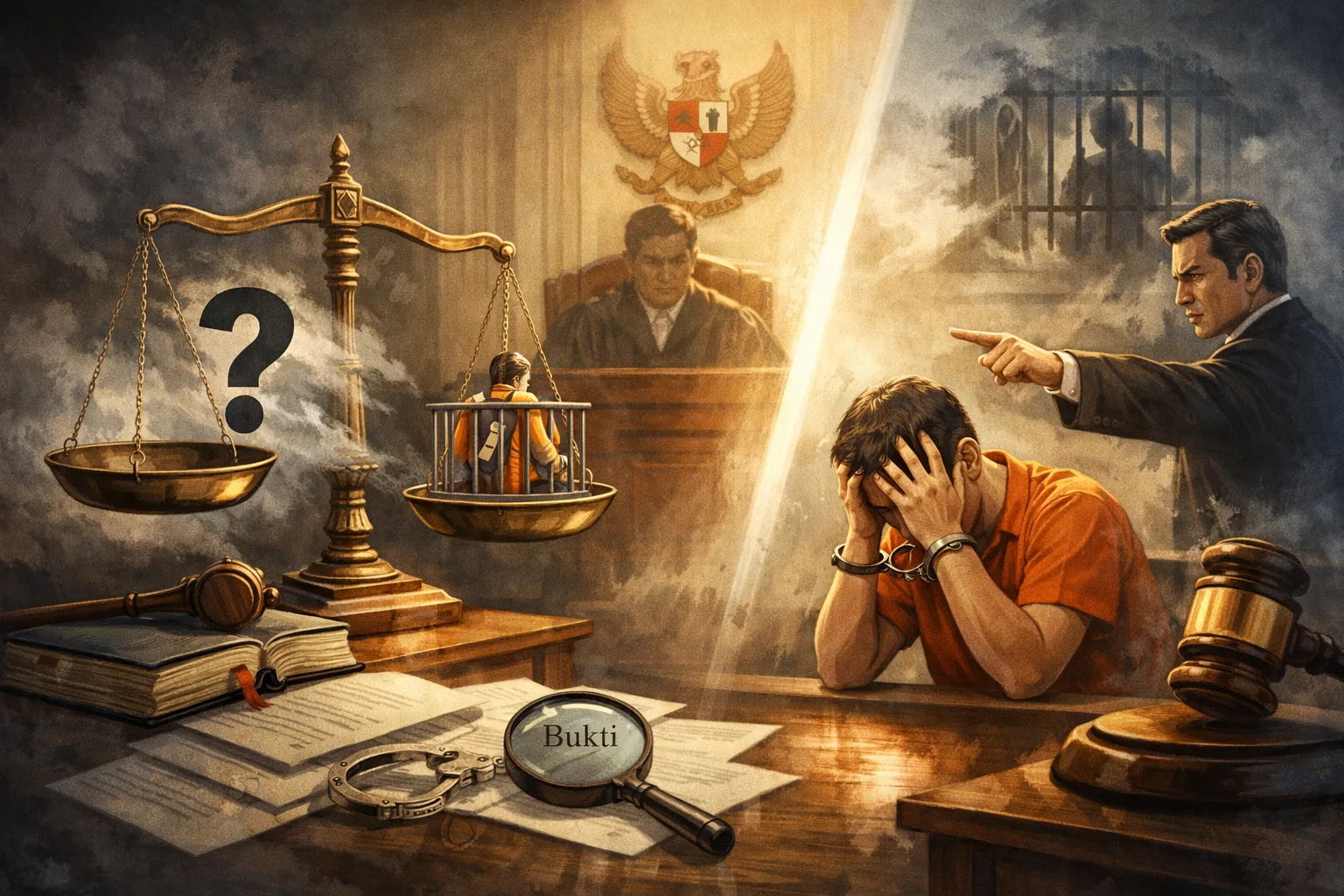

Considering this, the Constitutional Court could use a similar approach in the 2024 PHPU case. The similar approach referred to is the use of teleological interpretation in resolving the PHPU case. The complexity of the PHPU case demands a clear division and limitation of powers to prevent the centralization of power governing elections in one institution. Law Number 7 of 2017, as last amended by Government Regulation in Lieu of Law Number 1 of 2022 which was enacted into law by Law Number 7 of 2023, has detailed regulations accompanied by the division and limitation of these powers. The juridical implication is that the complexity of the PHPU case can be mapped clearly and comprehensively.

In the nuances of the complexity of this PHPU case, one of the institutions that has been in the spotlight besides the Constitutional Court is Bawaslu. The institution authorized to oversee the election process has a central position because it is authorized to prevent and follow up on TSM violations in elections. Thus, when a TSM violation occurs in an election, only Bawaslu has the authority. This is as regulated in Law Number 7 of 2017 Article 93-96.

The juridical implication is that the Constitutional Court is not authorized to enter this realm so that the authority of state institutions does not become mixed up. The sad thing is that TSM fraud cannot be prosecuted before the Constitutional Court, leaving the impression that the fraud has not been completely resolved. This is because Bawaslu is already in charge of supervising and following up on fraud in and during the election process. Furthermore, Constitutional Justice Ridwan Mansyur stated that the Constitutional Court only has the position to ensure that Bawaslu has carried out its duties and does not have the right to go any further.

This can actually be resolved by first interpreting the Constitution and the Law governing this authority. As explained above regarding Decision Number 138/PUU-VII/2009, the Constitutional Court first provided a teleological interpretation of the Constitution before deciding the a quo case. In the a quo case, the Constitutional Court conducted a judicial review of the Government Regulation in Lieu of Law, while the Constitution did not attribute this authority to the Constitutional Court. To overcome this, in the a quo decision, teleological interpretation was used by the Constitutional Court and an extension of the Constitutional Court's authority occurred.

The teleological interpretation in the settlement of the 2024 PHPU case is to view the Constitutional articles that give authority to the Constitutional Court from a teleological perspective. The Constitutional Court can abandon the use of grammatical interpretation by uncovering the purpose of the Constitutional articles giving the authority to handle the PHPU. Grammatically, Article 24C paragraph (1) "The Court has the authority...to decide disputes regarding the results of general elections" only gives the Constitutional Court authority related to resolving results, not the process. However, if viewed teleologically, the a quo Article can be seen as an order to the Constitutional Court to resolve any election disputes, whether in the form of results or processes. This is logical because without the process being resolved first, it will not produce good results.

Considering the aforementioned explanation, it is reasonable and possible for the Constitutional Court to follow the a quo decision in resolving the 2024 PHPU (Dispute over General Election Results). By following the legal reasoning used in the a quo decision, the Constitutional Court can first extend its authority so that it is authorized to address election cases affected by widespread (TSM) violations. If this occurs, it will certainly greatly influence the dynamics of law and constitution in this beloved country.

Regardless of all of that, the decision issued by the Constitutional Court must be respected and implemented by all parties. Furthermore, there are no further legal remedies that can challenge the Constitutional Court's decision because the Constitutional Court's decision is a decision at the first and last level, or final. This indicates that the Constitutional Court's decision is final and binding. Like it or not, the Constitutional Court's decision must be respected and implemented without any legal process that can disturb it.

Bibliography

- Martitah. (2023). The Constitutional Court from Negative Legislature to Positive Legislature. Jakarta: Konstitusi Press.

- NNC. (2007, November 27). Three Times the Same, Does the Constitutional Court's Decision Become Fixed Jurisprudence? Retrieved from hukumonline.com: https://www.hukumonline.com/

- Palguna, I. D. (2020). The Constitutional Court & the Dynamics of Legal Politics in Indonesia. Depok: Rajawali Press.

- Talmadge, P. A. (1999). Understanding the Limits of Power: Judicial Restraint in General Jurisdiction Court Systems. Seattle University Law Review, 711.

[1] Wicaksana Dramanda, “Proposing the Application of Judicial Restraint in the Constitutional Court”, Jurnal Konstitusi Vol. 11 No. 4, 2014, p. 620

[2] Phillip A. Talmadge, “Understanding the Limits of Power: Judicial Restraint in General Jurisdiction Court Systems”, Seattle University Law Review No. 695, 1999, p. 711.

[3] I D.G Palguna, The Constitutional Court and the Dynamics of Legal Politics in Indonesia (Depok: Rajawali Pers, 2020); 1st printing, p. 104

[4] NNC (2007) “Three Times the Same, Does the Constitutional Court's Decision Become Fixed Jurisprudence?”; accessed on April 22, 2024 from https://www.hukumonline.com/

Comments (0)

Write a comment