Demanding the Promise of Digital Public Participation: Evaluation and Reform of E-Participation in Indonesian Legislation

Legal Literacy - The Constitutional Court (MK) Decision Number 91/PUU-XVIII/2020 became a milestone in Indonesian legislative democracy. For the first time, the concept of public participation...

Table of Contents

- The Grim Reality of E-Participation in Indonesia

- Regulatory Ambiguity: Three Platforms, Zero Legal Certainty

- One-Way Communication: Participation as a Mere Formality

- Learning from Global Practices: Three Successful E-Participation Models

- Finland: The Power of Citizens' Initiative

- United States: Transparency Through Open Government

- European Union: Structured Openness Through "Have Your Say"

- Redesigning Indonesian E-Participation: Four Pillars of Reform

- Strengthening Integrated Infrastructure and Regulations

- Adopting Citizen Initiative and Crowdsourcing Models

- Regulating Participation Time and Stages

- Building Two-Way Dialogue and Feedback

- Conclusion: From Digital Formality to Substantive Democracy

- Source

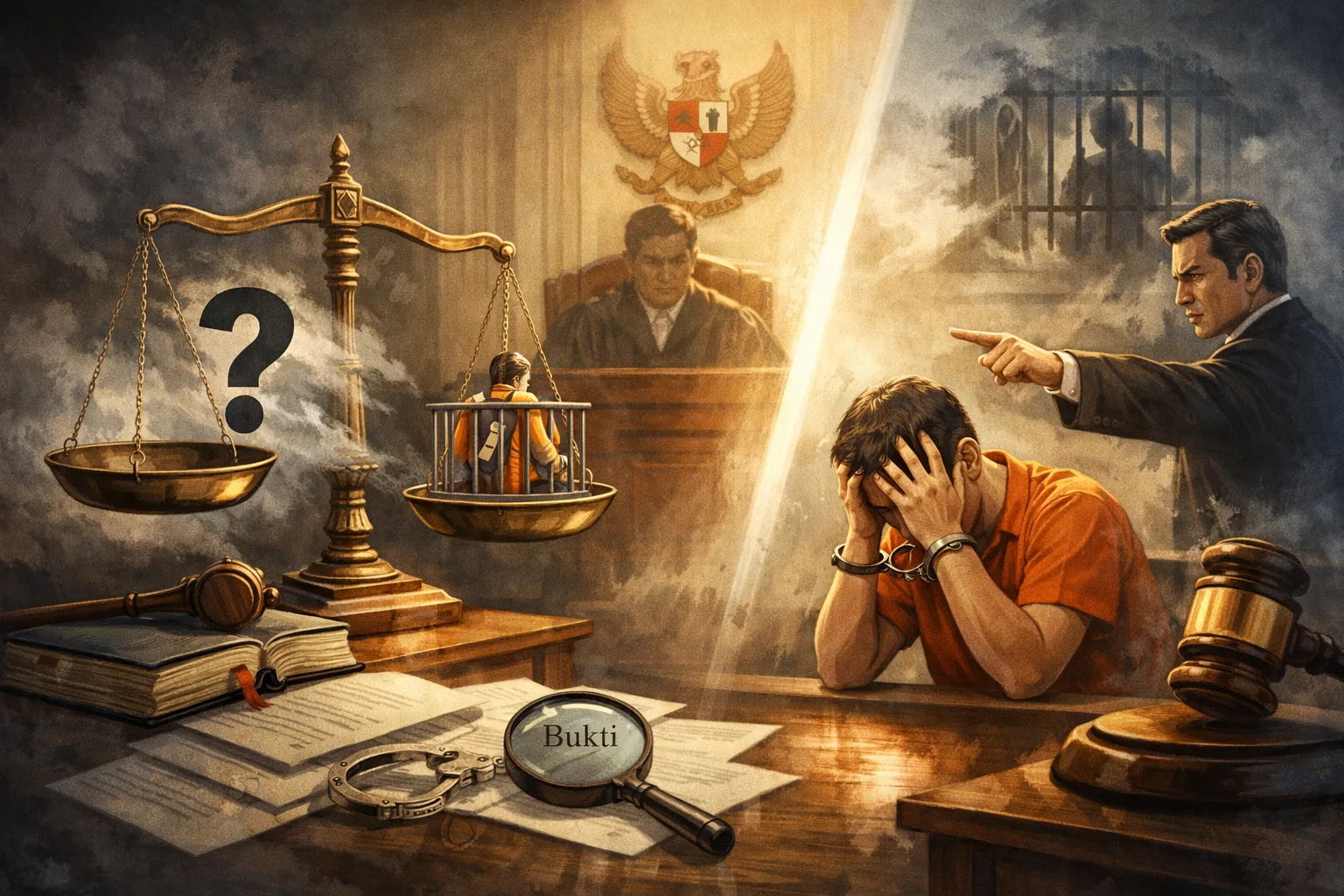

Legal Literacy-The Constitutional Court (MK) Decision Number 91/PUU-XVIII/2020became a milestone in Indonesian legislative democracy. For the first time, the concept ofmeaningful public participation (meaningful participation)was affirmed as a constitutional obligation. The public is no longer merely involved as a formality, but must be given the right to be heard (right to be heard), the right to be considered (right to be considered), and the right to be explained (right to be explained).

Following up on this decision, Law Number 13 of 2022 was born, which explicitly opens the door for online public participation, or what is globally known ase-participation. The hope is that information and communication technology (ICT) will become a bridge that brings the people closer to their representatives, creating a more transparent, inclusive, and responsive legislative process. However, after several years, the promise of digital participation still feels far from expectations. Various participation portals built by the government and the DPR appear deserted, and substantial dialogue between policymakers and the public in cyberspace is almost unheard of.

So, why are these digital channels not yet effective? What are the fundamental problems that hinder the realization ofe-participationin Indonesia? This article, referring to an in-depth analysis by Mochamad Adli Wafi and Muhammad Machshush Bill Izzi, will evaluate the bleak portrait of the implementation ofe-participationcurrently, comparing it with successful practices in other countries, and formulating four pillars of reform to claim the promise of true digital participation.

Support

• Indonesian Legal Literacy

Read more comfortably, while supporting literacy.

Join Membership or submit your article for publication.

Membership

Read without ads, more focused, and access premium features.

Submit Article

Submit your writing—we curate and help publish it. If published, you have the opportunity to earn points/payouts according to the provisions.

Comments (0)

Write a comment