Legal Literacy - October 12, 2002, became a dark mark in Indonesian history. The Bali Bombing I incident in the Kuta area, Bali, killed at least 202 people and injured more than 300 others. This tragedy not only tarnished Indonesia's image but also caused widespread fear of the threat of terrorism.

As a progressive response, the government issued Government Regulation in Lieu of Law (Perpu) No. 1 of 2002, which was later ratified into

Law Number 15 of 2003 concerning the Eradication of Criminal Acts of Terrorism.

However, a major controversy arose: this law was applied

retroactively to prosecute the perpetrators of the Bali Bombing (Amrozi, Ali Imron, Imam Samudra, et al.) for actions that occurred

before the law existed.

Violation of the Principle of Legality (Article 1 of the Criminal Code)

This retroactive application directly clashes with one of the most fundamental principles in criminal law:

Principle of Legality (

Nullum crimen sine lege).

This principle is clearly stated in

Article 1 paragraph (1) of the Criminal Code (KUHP):

"No act may be punished except by virtue of a criminal provision in legislation that existed before the act was committed."

Simply put, criminal law should not apply retroactively. The perpetrators of the Bali Bombings were tried using the 2003 Terrorism Law for acts they committed in 2002, when that specific law did not yet exist.

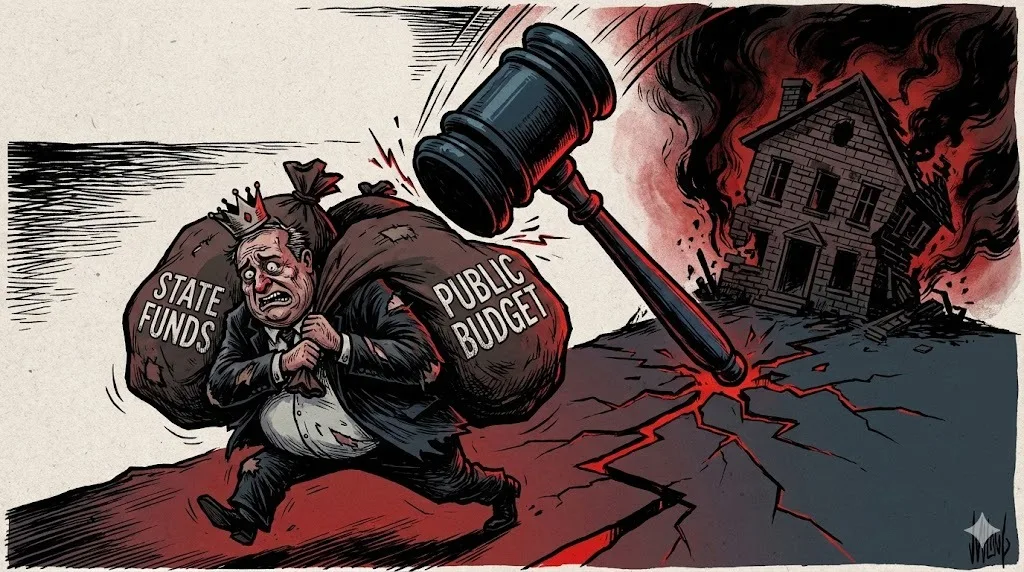

The government argued that the Bali Bombing tragedy was an

extraordinary crime. In criminal law doctrine, this status is intended for serious crimes such as terrorism, corruption, and gross violations of human rights.

These crimes are often handled with extraordinary legal measures (

extraordinary legal measures), including, in some cases, the use of retroactive laws. This justification is based on the state of emergency theory (

state of emergency theory), which refers to the adage:

"Salus populi suprema lex esto” (The safety of the people is the highest law).

With this justification, the state felt it necessary to take special measures for national security, which was ultimately used to impose the death penalty on the perpetrators.

Non-Retroactive Rights: Absolute Violation of Article 28I of the 1945 Constitution

The sharpest criticism of this move comes from a constitutional perspective. The enactment of

retroactive principle in the case of the Bali Bombings, it was considered to have violated the most fundamental human rights.

Article 28I paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution states:

"The right to life, the right not to be tortured, the right to freedom of thought and conscience, the right to religion, the right not to be enslaved, the right to be recognized as a person before the law, and the right not to be prosecuted on the basis of retroactive law are non-derogable human rights under any circumstances."

This article affirms that the right not to be prosecuted by retroactive law is a

non-derogableright, which is a right that cannot be reduced or violated by the state, even in a state of emergency.

Even international instruments such as

Article 15 of the ICCPR only allow non-retroactive exceptions for crimes already considered criminal under general international law (such as genocide or war crimes), where terrorism (at that time) was not necessarily included in that classification.

Academic Criticism and International Comparisons

This retroactive step has drawn strong criticism from academics and legal practitioners:

- Muladi (2005) stated that the enactment of retroactive law cannot be justified except in extraordinary circumstances that must go through strict constitutional mechanisms.

- Romli Atmasasmita (2004) criticized this step because it threatens legal certainty (rule of law) and has the potential to become a bad precedent.

In comparison, other countries strictly adhere to the principle of non-retroactivity:

- United States: The Constitution (Article I, Section 9) explicitly prohibits ex post facto laws.

- Germany & France: Their Constitutional Courts reject retroactive application unless it refers to pre-existing universal principles of international law.

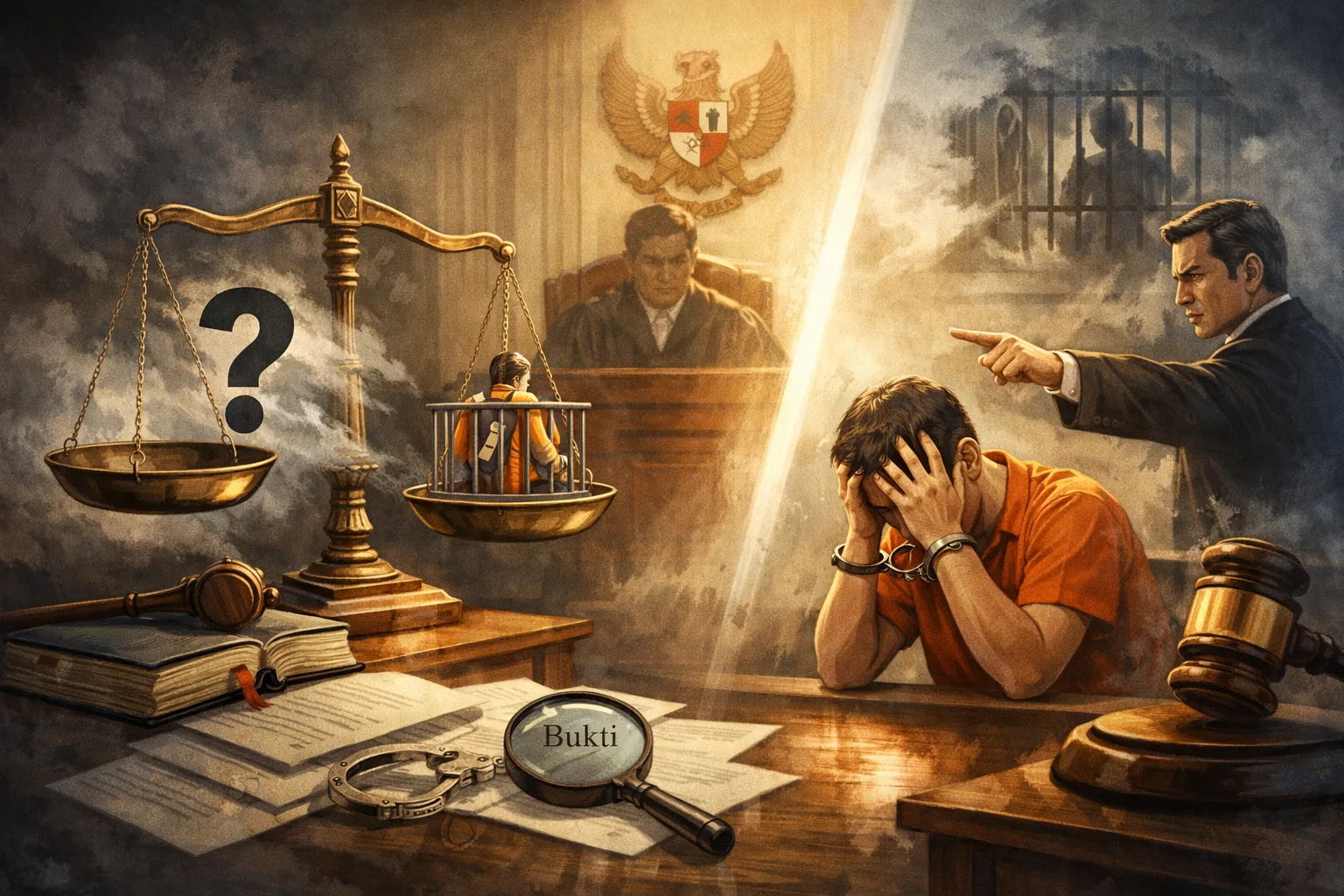

Long-Term Implications: Substantive vs. Procedural Justice

This case reflects the enduring tension between

substantive justice (the public's moral imperative to punish perpetrators) and

procedural justice (adherence to due legal process).

In the theory of procedural justice (John Rawls, 1971), the means are as important as the ends. The legitimacy of a legal system is built upon consistent rules. When the state violates its own rules (Article 1 of the Criminal Code and Article 28I of the 1945 Constitution) for the sake of an outcome, it undermines public trust and

rule of law.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The retroactive application of the law in the Bali Bombing case, although based on the need to combat terrorism, is juridically contrary to the principle of legality (Article 1 of the Criminal Code) and violates non-derogable constitutional rights (Article 28I of the 1945 Constitution).

This disregard for the principle of legality sets a negative precedent for the Indonesian rule of law. Based on this analysis, here are some recommendations:

- For Legislators: An evaluation and updating of criminal law instruments is necessary to be prepared to face extraordinary crimes in the future without having to sacrifice fundamental legal principles (the principle of legality).

- For Law Enforcement Officials: It is mandatory to uphold the principle of legality and prudence in interpreting authority so as not to violate the constitutional rights of citizens.

- For Academics/Practitioners: It is necessary to continue to conduct critical studies of law enforcement practices that have the potential to deviate from rule of law to strengthen the national legal system.

Comment (0)

Write a comment