Legal Literacy - Imagine a morning in the office public service where a citizen has to wait for hours only to be told that the authorized official is in a "meeting", while behind the counter glass, piles of files that should have been completed yesterday are left to gather dust. This scene is so common, so banal, that we tend to accept it as a "risk of life" in this country. However, behind the lethargic face of bureaucracy, there is a large sore that in our legal discourse we call maladministration. The problem is, in our legal governance, maladministration is often only considered a "typo" or "procedural negligence" that is forgiven with a formal apology or a verbal reprimand that leaves no trace. When practices like this are accepted as commonplace, the state is actually teaching one dangerous thing: that negligence of power is not a mistake, but a tradition. Maladministration is not just a procedural failure, but an offense of power legalized by custom.

Maladministration as an Offense of Power in the Rule of Law

Every government action, no matter how small, is essentially an extension of power that must be subject to the law. As emphasized by Hadjon (2007: 95), every government action must be legally and morally accountable because it concerns the use of authority derived from the people's mandate. Therefore, if we delve deeper into the recesses of legal philosophy, maladministration is actually the most obvious form of betrayal of the social contract. When the state fails to provide proper services, it is actually systematically violating the constitutional rights of citizens. We need to build a new legal construction: that serious maladministration is a convergence of unlawful acts by the authorities (onrechtmatige overheidsdaad), gross negligence, and violations of citizens' constitutional rights. In perspective of state administrative law, compliance with the General Principles of Good Governance (AAUPB) is not an option (optional), but an obligation (imperative).

As Ridwan (2016: 182) asserts, AAUPB is a benchmark for the validity of government actions; without it, we will only be trapped in a condition of a "shameless state," a condition in which violations of procedure are considered a normal propriety.

Normalization of Negligence and the Collapse of Legal Dignity

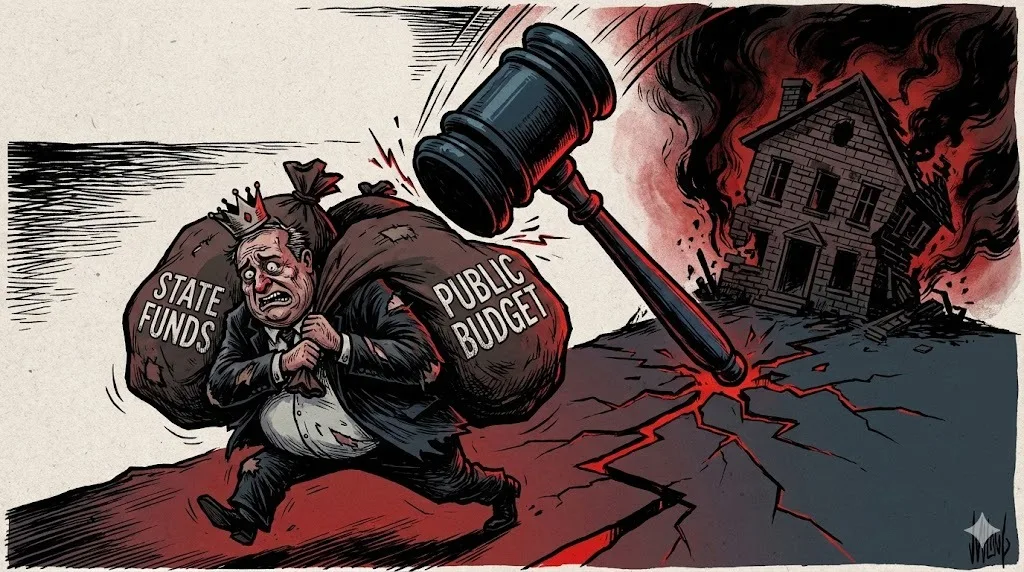

In the midst of this banality, we need to pause for a moment and ask questions that challenge the existence of our law. If maladministration that violates constitutional rights is not considered a serious offense, then what law are we actually protecting? If a small citizen is punished for stealing a pair of sandals for survival, while an official who emasculates the rights of thousands of people through a procedurally flawed decree can still walk away without any sanctions other than an "administrative reprimand," where is the dignity of our law? This inequality shows that we are maintaining a system that values the formality of office more than the substance of justice. We are trapped in the narrow logic that "crime" only occurs if there is an illegal flow of funds, while the practice of killing legal certainty through maladministration is considered a residue of development that can be morally justified.

The Ombudsman and the Culture of Administrative Impunity

Our lack of seriousness in addressing maladministration is evident in how our legal instruments operate in a discriminatory manner. Law Number 37 of 2008 concerning the Ombudsman of the Republic of Indonesia does provide a supervisory mandate, but the institution's fangs are often blunt when faced with the sectoral ego walls of ministries or institutions. The Ombudsman's recommendations, which are legally final and binding, are often regarded in practice as "friendly advice" that can be ignored without consequence. This condition creates a culture of impunity. If an official commits an administrative error that causes billions of rupiah in losses to citizens' rights, but no money goes into their personal pocket, our law tends to hesitate to punish them. In fact, the destructive impact of an administratively flawed decision is often broader and more permanent than a single act of individual bribery. Administrative offenses of office are the most ancient form of malpractice of power because they extinguish the people's hope for justice right at the doorstep of government offices.

Official Discretion and the Legal Limits of Abuse of Authority

However, in order to maintain the clarity of the law and avoid shallow populism, we must be able to rigidly distinguish the hierarchy of administrative errors. We need to separate between minor administrative errors that are technical-clerical in nature, serious errors that injure service procedures, to gross administrative misconduct that consciously violates constitutional rights or abuses authority in an extreme manner. It is important to emphasize that the discretion of officials remains protected by law as a space for service innovation (freies ermessen). Legal problems arise not when officials take discretion, but when that discretion deviates from the original purpose of granting authority (détournement de pouvoir). Discretion is a tool to achieve benefit, but it must not become a shield to legalize arbitrariness. Minor errors may be resolved with administrative improvements, but serious maladministration must be positioned as an offense of power that cannot simply be redeemed with an apology.

Reformulation of Sanctions against Serious Maladministration

Therefore, it is time for us to radically redefine the governance of power. We must begin to view maladministration as an administrative offense of office that has a degree of danger equivalent to corruption. This transformation requires a paradigm shift from persuasive supervision to coercive supervision. Recommendations from the Ombudsman should no longer end up in the archives. There must be a legal mechanism that automatically links non-compliance with recommendations to severe administrative sanctions, including removal from office or disqualification from public office in the future. We need to implement "Sanctions of Shame" institutionally, where agencies that continuously commit maladministration are given a red label publicly. Of course, this mechanism must still be subject to due process of law, strict proof of negligence through independent audits, and full transparency to avoid new abuses of authority within the supervisory body itself.

Furthermore, our biggest challenge is to tear down the wall of "blind loyalty" within the bureaucracy. The rule of law can only be achieved if procedures are carried out with moral integrity. Often, maladministration occurs because subordinates are afraid to question the orders of superiors that clearly violate procedures. This is exacerbated by the neglect of living law that develops in society. The Constitutional Court, in several of its decisions, has implicitly begun to place the right to good public services as part of the fulfillment of human rights. Therefore, the protection of whistleblowers within the bureaucracy who dare to report administrative offenses must be legally strengthened. We need bureaucrats who are more afraid of the law than afraid of the anger of their superiors. The collective awareness that public service is a sacred trust must be re-instilled since education in public service. Without this moral transformation, even the greatest regulations will only become beautiful paper tigers that have no fangs to bite deviations.

Compliance with PTUN (State Administrative Court) Decisions as a Test of the Rule of Law

The discourse on the "Shameless State" must also touch on the role of administrative justice, which has so far felt isolated. So far, the State Administrative Court (PTUN) has been more concerned with the annulment of decisions (beschikking) than with providing full restoration of citizens' rights. If a citizen wins a lawsuit in the PTUN, they often only get a victory on paper because the execution of the decision depends heavily on the "good faith" of the official concerned. Asshiddiqie (2010: 58) states that the legal dignity of a country is at stake in how its court decisions are respected. Executive non-compliance with the judiciary in administrative matters is the highest level of power offense, a constitutional rebellion that injures the principle of separation of powers and destroys legal authority in the eyes of the public. When court decisions are ignored by the authorities, then the law is actually being declared dead by the state itself.

Restoring Shame in Public Service

As an offer of progressive yet original ideas based on sound legal principles, Indonesia needs the establishment of a "Public Service Court" or at least the strengthening of a special chamber in the Supreme Court that specifically handles citizen compensation claims due to severe maladministration. This compensation should not only be borne by the state, but should also be jointly and severally charged to the personal assets of officials proven to have committed abuse of power intentionally or through gross negligence. With personal financial risk proportional to the level of error, officials will have a strong incentive to comply with procedures. Of course, this policy should be limited only to cases where there is strong evidence of abuse of authority or intent to ignore established procedures. This is the most effective way to restore "shame" to the heart of our bureaucracy. There is no more room for inefficiency deliberately maintained at the expense of the people.

In closing this reflection, we must realize that a great nation is not measured solely by the magnificence of its physical infrastructure, but by how dignified it serves its simplest citizens. Maladministration that continues to be maintained is a poison that slowly but surely will paralyze our democracy. We must no longer allow this country to be managed by a "just get it done" mentality that ignores the procedural rights of citizens. The law must be present not only to punish petty thieves, but also to discipline negligent rulers. A state that tolerates maladministration is not actually failing to serve, but rather the most silent form of constitutional denial.

Comments (0)

Write a comment